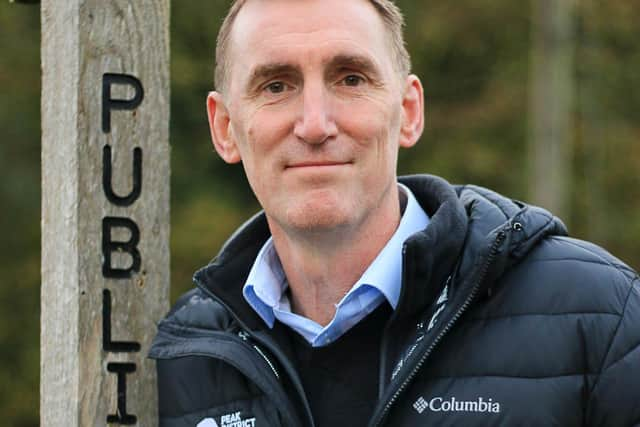

New Peak District chief talks funding, farming and the future of the national park

and live on Freeview channel 276

Phil Mulligan leads me into his office, a grand wood panelled room with high ceilings and expansive windows that look out over the leafy grounds of the Peak District National Park Authority (PDNPA) headquarters, in Bakewell.

“I don’t need an office this big,” he says humbly as he pours me a coffee.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe park’s new chief executive is no stranger to being in charge, having previously held high ranks at organisations including The Canal and River Trust, Environmental Protection UK and The Conservation Volunteers.

Phil has only been in this post for two months, having taken over from Sarah Fowler in September, and tells me he is still very much in the ‘listening and understanding’ phase.

“It’s a dream job,” he states when I ask what attracted him to the position.

“I want to be playing the biggest role I can in helping to address the nature crisis, climate emergency, the well-being crisis we have.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I want to be doing that in an inspiring place where my family can grow up.”

Advertisement

Hide Ad

It may be a dream job, but Phil is under no illusions about the amount of work that faces him as chief.

The authority, alongside the country’s other 14 national parks, has seen huge funding reductions in recent years and faces uncertainty over future support from a Government whose financial plans have proved inconsistent in recent months.

“We were given a flat cash settlement, which means we’re getting a real terms cut,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“We’re a relatively small part of Government expenditure that benefits 20 million visitors and residents, that can play a big role in water quality, carbon reduction and nature recovery.”

Phil believes national parks need to collectively make a case to Government for more cash to continue their important work, giving the Moors for the Future project as an example of a successful scheme that benefits the country as a whole.

Advertisement

Hide AdOriginally funded by the European Union, the project sought to restore upland moorlands with the aim of improving water quality, biodiversity and carbon capture, as well as increasing flood resilience by enabling water to drain into the valleys at a slower rate.

“It’s cheaper to do the upland restoration than it is to do a load of hard engineering concrete solutions downstream to do with flooding,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe country has made a commitment to 30 by 30, a promise to ensure 30 per cent of the UK is protected for the recovery of nature by 2030.

“The commitment is there, we now need the assurance, roadmap and policies in place to give all our partners the confidence and ability to deliver that,” Phil states.

Farmers too need assurance that funding will be in place to support them, and he comments that following Brexit the country has an opportunity to produce a new system that pays farmers for environmental returns.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe Farming in Protected Landscapes programme assists farmers to make changes to their working practices for the benefit of the environment.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“There are ways of farming to create more biodiversity and produce food,” Phil says, suggesting the introduction of trees to high grazing land to provide ‘wildlife corridors’ and increase biodiversity.

A popular spot for second homes and holiday lets, affordable housing in the Peak District has long been cause for concern among residents, with many young people being forced out by sky-high property prices.

Phil acknowledges the clash of ideologies between the desire to retain young people and protect the unique character of the landscape.

He says: “We don’t want the park to be a museum, but we also don’t want it to become an urban sprawl.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It’s designated as a national park for good reason, it is an outstanding landscape of national significant and we need to protect and maintain that.”

More than 30million people live within an hour’s drive of the park and Phil explains that one of the roles of the PDNPA is to ‘promote understanding’ among residents and visitors, commenting: “A lot of people will visit that have no idea what a national park is, they’ll not support the national park in any way, they may not even support local businesses, they may come with all their own food and drink.

“The more understanding there is of why this is special, the more care there will be, the more support there will be, and therefore the more sustainable the businesses will be and the communities who live here will be.”

Another challenge facing the park is the sparsity of public transport, meaning the majority of visitors travel by car, causing congestion and increased carbon emissions.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhile the PDNPA is not responsible for transport, it is currently working with partners, including bus operators, large attractions and neighbouring authorities, to try and come up with a solution to this problem.

Advertisement

Hide AdAs a father with a family in the process of relocating to the park, the chief feels the pull of the conflicting concerns of conservation and modern living.

“It’s going to be my home and I need it to be a thriving sustainable place for my young children and for my adult son who lives with me who’s going to need to find work, who’s going to be wanting to connect on the internet.”

Phil’s vision for the Peak District is a place that makes great strides towards environmental recovery for the good of the nation, while providing a haven for millions of visitors away from the mounting pressures of 21st Century life.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe says: “I see our purpose really being to show people where hope lies, to plant those seeds of passion and help protect the planet and just protect a landscape of ambition that shows people what the future holds.”